Abstract

Purpose

This review aimed to examine (a) trends in the number of publications on unmet needs over time and (b) the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce unmet needs among cancer patients.

Methods

An electronic literature search of Medline to explore trends in the number of publications on patients’ unmet needs and an additional literature search of Medline, CINAHL, PsychINFO, and Web of Science databases to identify methodologically rigorous research trials that evaluated interventions to reduce unmet needs were conducted.

Results

Publications per year on unmet needs have increased over time, with most being on descriptive research. Nine relevant trials were identified. Six trials reported no intervention effect. Three trials reported that intervention participants had a lower number of unmet needs or lower unmet needs score, compared to control participants. Of these, one study found that the intervention group had fewer supportive care needs and lower mean depression scores; one study found that intervention participants with high problem-solving skills had fewer unmet needs at follow-up; and one study found an effect in favor of the intervention group on psychological need subscale scores.

Conclusions

Reasons for varying results across trials and the limited effectiveness of unmet needs interventions are more broadly discussed. These include inadequacies in psychometric rigor, problems with scoring methods, the use of ineffective interventions, and lack of adherence to intervention protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Psychosocial impact of cancer and its treatment

The psychosocial impact of a diagnosis of cancer is widely acknowledged. Rates of clinically significant distress have been reported to be between 25% and 45% among people with cancer [1, 2]. Cancer treatment can bring about changes in body image and sexual functioning [3]. Symptoms, such as pain and fatigue, can lead to a diminished capacity to fulfill the usual social, vocational, and family roles [3]. The effects of cancer and its treatment may, therefore, be far-reaching, impacting on a person’s physical, social, and emotional well-being. As such, a broad range of services and support may be needed to assist patients and their families to manage these effects.

Unmet supportive care needs are prevalent among cancer patients

The term supportive care needs is an umbrella term which covers the physical, informational, emotional, practical, social, and spiritual needs of an individual with cancer [4]. Unmet supportive care needs (unmet needs) are those needs which lack the level of service or support an individual perceives is necessary to achieve optimal well-being [4, 5]. Measures of unmet supportive care needs are able to capture concerns across a broad range of domains reflecting the multidimensional impact of cancer [5, 6]. Cancer patients have reported high levels of unmet need related to issues such as provision of information [5, 7–9], psychosocial support [5, 8, 10, 11], practical assistance [12, 13], and sexual issues [11, 14]. Cross-sectional research has also indicated that reporting higher levels of unmet need is associated with increased anxiety and poorer quality of life (QoL) among patients [6, 13, 15, 16]. Measures have been developed for cancer patients undergoing treatment [17], terminally ill cancer patients [18], and cancer survivors [19], as well as caregivers [20–22]. The increased attention on measure development and description of unmet supportive care needs suggests that it is important to establish how these needs can be ameliorated.

Potential to reduce unmet needs through timely identification and tailored intervention

Typically, unmet need measures provide an indication of the relative importance of a need, rather than simply whether or not the need remains outstanding [23]. In this way, unmet need measures help to provide an indicator of an individual’s judgment regarding the significance of the need in relation to their psychosocial well-being. For researchers, clinicians, or other administrators, this method may also inform service prioritization [6, 24, 25].

It is plausible that unmet needs can be addressed through timely identification and provision of appropriate services or interventions. Given this potential, it is not surprising that research efforts have been directed towards the development and evaluation of interventions to reduce unmet needs among people with cancer. The aim of this review was to examine (a) trends in the number of publications on unmet supportive care for people with cancer since 2000 and (b) the effectiveness of all previous interventions developed to reduce unmet needs among people with cancer that employed methodologically rigorous study designs.

Methods

Definition of unmet needs

For the purpose of this review, an unmet need was defined as a necessary or desired action or resource that is required in order to achieve optimal well-being [5, 26].

Aim 1: examining trends in the number of unmet needs publications over time

Literature search

An electronic literature search was conducted using Medline using the terms “Health Services Needs and Demand or Needs Assessment or needs assessment.mp” OR “unmet needs.mp” AND “cancer.mp or Neoplasms.” Additional limits included publications between 2000 and 2010 and “all adult (19 plus years).” This search was restricted to one database only, as the intention was to provide an overview of trends only rather than a comprehensive search. The year 2000 was chosen as the beginning parameter of the search as several seminal papers were published on the unmet needs of cancer patients in this year [5, 17, 27]; therefore, it would be expected that interest in needs publication would increase from this point onwards.

Inclusion criteria for examination of trends in the number of publications on unmet needs

To provide an overview of the trends in the number of unmet needs publications over time, abstracts from Medline were reviewed. Studies which reported primary data on unmet supportive care needs for cancer patients or survivors were included. Both qualitative and quantitative published data were included. Studies were classified as “measurement” if they reported on the development or testing of a measure of unmet supportive care needs for people with cancer, “descriptive” if they reported on the prevalence or type of unmet needs experienced by people with cancer, or “intervention” if they reported on the evaluation of an intervention to reduce unmet supportive care needs.

Aim 2: systematic review of intervention studies

Literature search

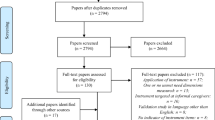

An electronic literature search was conducted using Medline, CINAHL, PsychINFO, and Web of Science databases on 12 January 2011. The following combination of search terms was used: “intervention.mp OR intervention studies” OR “clinical trial(s)” OR “randomized controlled trial” AND “health services needs and demand” OR “health service needs” OR “needs assessment OR unmet needs.mp” AND “cancer.mp or neoplasms.” The search was limited to “all adults (19 plus years).” Researchers known to be conducting work in the area of unmet needs were also contacted by the authors to identify any additional publications which were under review or in press.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Publications were eligible for inclusion if they (a) tested the efficacy of an intervention to reduce unmet needs among adult cancer patients or survivors, (b) used a validated quantitative measure of unmet needs as the primary or secondary outcome, and (c) used a methodologically rigorous research design. The following research designs were included [28]:

Randomized controlled trials

These are studies where participants were randomly assigned to intervention or control groups.

Quasi-randomized controlled trials

These are studies which included a concurrent control group and where alternate assignment (or some other non-random method) was used to assign participants to intervention and control groups.

Controlled before and after designs

These are studies where measures were collected at an intervention and control site contemporaneously both before and after the intervention.

No restrictions on date of publication were used. Papers that were published in languages other than English; were dissertations, conference abstracts, or study protocols; were not relevant to cancer patients or survivors; were focused on children or adolescents with cancer; and were interventions that aimed to change provider behavior were excluded.

Assessment of publications against the inclusion criteria

Two authors independently examined all retained abstracts to identify publications that reported the results of methodologically rigorous intervention studies. Full-text versions of the remaining papers were reviewed independently by two authors to exclude intervention papers which were either not relevant to unmet needs or did not use a validated, quantitative measure of unmet need. Studies were then coded against the following quality criteria: concealment of allocation, whether outcomes were similar across groups at baseline, whether missing data were likely to affect results, and whether participants were blind to study allocation. Any discrepancies were discussed until an agreement was reached. The two authors then extracted the following information for each trial: aims and study design, setting and sample, description of the intervention, outcome measures used, and intervention results.

Results

Aim 1

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the majority of these studies have utilized descriptive methods, as opposed to measurement or intervention research. Despite some fluctuation, the number of descriptive studies per year has substantially increased from 2000 to 2010, while the number of intervention studies per year has remained low.

Aim 2

As shown in Fig. 2, eight studies from the literature search met the inclusion criteria. One additional randomized controlled trial (RCT) was identified through the authors’ research networks [29]. A high level of inter-rater agreement between the two authors for all coding stages was indicated by a kappa of 0.95. The study characteristics of the nine included trials are presented in Table 1.

Study design

Two studies used a quasi-randomized controlled design, and the remaining studies were RCTs.

Concealment of allocation

Patients were the unit of randomization in all studies. Four of the seven RCTs reported that allocation was concealed when eligibility was being assessed [29–32].

Baseline measurements similar

All studies reported that outcomes of interest were similar across groups at baseline, with the exception of the Scandrett study which reported that intervention participants had more needs than control participants in seven content areas [33].

Missing data unlikely to affect results

Missing data were adequately addressed in four studies [29, 31, 34, 35]. In King’s RCT [32], loss to follow-up was greater in the 2 intervention arms (16 and 12 participants, respectively) than in the control group (4 participants). In the remaining studies, insufficient information was provided to determine whether missing data were likely to affect results.

Knowledge of allocation to the intervention concealed

Only one study indicated that participants were blind to their allocation to the intervention or usual-care group [33].

Setting and sample

All studies reported that participants were cancer patients. Five studies included more than one cancer type in the sample [31–33, 35, 36]. The remaining four studies focused on specific types of cancer including breast cancer [30, 37] and colorectal cancer [29, 34]. Three studies recruited participants from population-based cancer registries [29, 31, 34], one recruited oncology inpatients [33], and five recruited participants from outpatient cancer clinics [30, 32, 33, 35–37].

Descriptions of interventions

With the exception of one study [37], all of the reviewed intervention studies included an initial identification of patient unmet needs, with feedback of identified needs provided to a health professional and/or the patient. Five of the studies included a structured clinical response intervention, tailored to address individual patient needs [29–31, 34, 35]. Four of the interventions were delivered face-to-face only [32, 33, 35, 36], with the remainder delivered either by telephone only [29, 34] or a combination of face-to-face and telephone delivery [30, 31, 37]. Intervention agents included nurses [30, 32, 35, 37], physicians [36], general practitioners [31], trained volunteers [29, 34], telephone caseworkers [31], and multidisciplinary teams [33]. In some of the studies, there was more than one type of professional serving as the intervention agent. For instance, in the study by Girgis and colleagues, the intervention in arm 1 was delivered by a telephone caseworker, while the intervention in arm 2 was delivered by the patient’s general practitioner [31].

Outcome measures

Four studies used the original Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS) [29, 30, 32, 34]; two studies used the short form of the SCNS (SCNS-SF34) [31, 36], with one of these also using the Needs Assessment for Advanced Cancer Patients (NA-ACP) [31]; one study used the Cancer Rehabilitation Evaluation System (CARES) [37]; one study used the Needs of a social nature; Existential concerns; Symptoms; and Therapeutic interaction scales (NEST13) [33]; and one study used an earlier version of the SCNS, the Cancer Needs Questionnaire short form (CNQ) [35].

Effectiveness of unmet needs interventions for cancer patients

Six of the nine studies—four high-quality, large-scale trials [29, 31, 33, 35] and two pilot studies with fewer than 50 participants per group [32, 36]—failed to show a reduction in unmet needs for patients receiving an intervention, compared to usual care, at any follow-up time point. The remaining three studies found some intervention effect [30, 34, 37]. Aranda and colleagues’ trial of a nurse-led intervention, which focused on the development of self-care strategies for advanced breast cancer patients, demonstrated an effect on the psychological unmet needs subscale only of the SCNS for those patients who reported high unmet needs at baseline [30]. Similarly, post hoc subgroup analysis identified an intervention effect for those with high problem-solving skills at baseline in Allen’s trial [37]. A small pilot study undertaken by Macvean and colleagues reported a lower prevalence of overall unmet needs for colorectal cancer patients receiving an intervention [34]. However, these finding were not replicated in the full-scale trial [29]. Of those reporting an effect, no studies used the same unmet need measure or reported an intervention effect in the same unmet need domain.

Discussion

This review demonstrated that there has been increasing attention to unmet needs of cancer patients in the literature over time, with greater attention given to descriptive studies than intervention studies. While the literature search describing trends in types of unmet need publications was not intended to be systematic, the focus on descriptive research is concerning. Descriptive research has been invaluable in highlighting the unique needs of cancer patients and the necessary urgency to ameliorate these issues [5, 7, 9, 13]. It is generally accepted that the process of conducting descriptive research is simpler than for intervention studies, in terms of conceptualization, feasibility, and publishing [38]. While this may explain the trends observed in unmet needs research, it raises several issues. If it is not possible to change unmet needs, then there may be limited value in continuing to describe these needs. Conversely, if it is possible to change unmet needs, it could be argued that a greater emphasis on evaluating the effectiveness of strategies is warranted. A more appropriate balance in research effort is necessary to capitalize on available research funding, to develop a best-practice evidence base, and most importantly, to improve the psychosocial outcomes of cancer patients.

A total of nine intervention studies were identified. Six of the nine trials included in this review failed to demonstrate an intervention effect on unmet needs. Therefore, the results of this review suggest that, while it may be possible to reduce some patients’ unmet needs through supportive discussions, therapies, or referral, these changes have not been consistently demonstrated. Results of the reviewed intervention trials do not provide strong evidence for any particular approach for reducing levels of unmet need. In particular, testing of multiple subscale scores at multiple time points and the use of post hoc subgroup analyses in two of the three positive trials suggest the possibility of spurious results arising from type II errors [30, 37]. The third trial was a pilot study [34] and, although it demonstrated an intervention effect, this was not replicated in the full-scale RCT [29]. Given increasing interest in the assessment of and use of unmet needs measures for screening and tailoring interventions, it is timely to consider which factors may contribute to the mixed and limited findings observed across trials.

Potential explanations for mixed findings among intervention trials which aim reduce unmet needs among cancer patients

Psychometric rigor of unmet needs measures

While measures such as the SCNS have been psychometrically tested for validity and reliability [17, 39], sensitivity to change over time has not been well explored [6, 40]. It is possible that current measures of unmet need are not sufficiently sensitive to consistently identify small or isolated changes in unmet need. This may be due to the fact that these tools were originally designed to capture a wide breadth of concerns across an entire population, rather than being sensitive to the particular needs of an individual. Such psychometric design attributes may, therefore, limit the use of these instruments as individual screening devices or intervention outcome measures.

Appropriateness of measures for the selected sample

It should also be noted that, while all studies included in this review used the term “cancer patient,” some of the samples included may have consisted of cancer survivors. While definitions of survivorship vary [41, 42], treatment completion is often used as a defining point [43]. In particular, for the three studies that reported recruitment via population-based cancer registries [29, 31, 34], participants were at least 4–6 months post diagnosis at the time of study entry, and current treatment status was not clearly reported. It is, therefore, likely that many of these participants may have been “survivors” rather than patients. Since the needs of cancer survivors are known to be different from cancer patients [44], this suggests that studies which include survivors should use needs measures which have been specifically developed for the survivor population [6]. The SCNS, used in all three of the latter studies, was developed for a patient population (undergoing treatment) rather than a survivor population (post-treatment) [17]. Therefore, this measure may not have been appropriate to adequately capture the needs of these groups. Future research with cancer survivors should use measures specifically developed for this population such as the Survivors Unmet Need Survey (SUNS) [19] or the CaSUN [45].

Study samples are insufficient to find an intervention effect

It may be that, when using wide-ranging unmet needs measures such as the SCNS or CNQ, or for potentially heterogeneous samples involving multiple cancer types, large samples are required to identify small changes in particular patient needs. These measures may be more suited to identifying small changes in the population prevalence of domains of unmet need, rather than identifying small patient-specific changes. However, this theory is not supported by the studies reviewed here, given that the study with the largest and potentially most homogenous sample failed to find an effect [29].

Analysis of unmet needs

Items in unmet need measures can potentially be analyzed in a number of ways, and the scoring and analysis of these measures have evolved over time. Most studies in this review used domain scores as their outcome measure. On both the NA-ACP and the SCNS, domain scores are calculated by summing item scores [18, 46]. Therefore, similar scores at two follow-up points may not necessarily reflect that participants are endorsing the same needs at both time points [23]. Similarly, the approach of using subscale scores does not allow determination of whether specific needs have been reduced over time as a consequence of the intervention. Similar problems arise when the number of needs endorsed as unmet is used as an outcome measure rather than a domain score. This may hide the fact that needs may change over time, with different needs contributing to the prevalence count for an individual at any given time point.

An alternative to using subscale scores may be to examine changes in specific items of unmet needs. Without evidence of test–retest reliability at the item level, however, examining changes in prevalence of need by item is also problematic. Item-level test–retest reliability has not been demonstrated for any unmet needs measures for adult cancer patients [40]. This means that it is impossible to tell whether any change in number of people endorsing an item is due to the intervention or lack of test–retest reliability in the item.

Interventions tested are ineffective

It is possible that limited intervention effects observed across trials are a result of ineffective interventions. Descriptive studies have indicated that a range of sociodemographic, disease, physical, and psychological factors are associated with unmet needs [16]. Lack of effect may, therefore, indicate that the intervention is not powerful enough to address the many factors that may influence unmet needs. Similarly, the “dose” of the intervention may also have been inadequate to achieve an effect. A recent meta-analysis has found that longer-term interventions (minimum 12 weeks) had a greater impact on QoL of adults with cancer than short-term interventions (d = 1.19, d = 0.47) [47]. Intervention intensity and frequency were quite varied across the studies reviewed, ranging from single assessment and printed feedback to multiple sessions and multiple referrals. It is, however, difficult to assess the true intensity of any particular intervention, given that referral or feedback were a key part of the majority of both the effective [30, 34] and ineffective interventions [31–33, 35, 36]. Limited data were provided on the consequences of the referrals. It is highly likely that this was variable both within and between studies.

Interventions are not delivered as intended

Lack of intervention effect may also reflect lack of adherence to key intervention components by patients or providers. For example, in McLachlan’s study, recommended services from the tailored management plan were declined by patients in 38% of instances [24]. Reasons reported for refusal of services included inappropriate timing of the referral and preferences for other forms of support including other formal services and informal support of self-management [24]. Similarly, in Boyes’ pilot study, only two of the four doctors involved in the study reported that they had discussed the feedback on needs with their patients during the consultation [36]. Given this low level of adherence to the intervention, the lack of effect may not be surprising.

Floor effects preclude demonstration of an intervention effect

Post hoc analysis in Aranda’s study indicated that an intervention effect may be possible if those who have high unmet needs at baseline are selectively targeted [30]. Similarly, Girgis and colleagues noted that participants in their trial reported higher levels of QoL and psychological well-being than expected [31]. The authors suggested that this may have contributed to the lack of intervention effect observed. This echoes a common criticism of psychological interventions to reduce distress, anxiety, and depression among cancer patients, whereby interventions to improve these outcomes are targeted at all patients rather than at those with demonstrated need at baseline [48]. This may reflect an assumption that all people with cancer have high levels of unmet supportive care needs.

However, selective targeting of high needs individuals poses its own challenges. These difficulties may include logistic and cost difficulties in screening large numbers of patients to identify a subset requiring intervention prior to commencing a trial. It may also reflect that there is no clear threshold for needs measure, which indicates clinical significance [23]. Therefore, by arbitrarily excluding those below a certain score, it is possible that some people who may benefit from an intervention may be excluded. Research focusing on the establishment of clinical significance of need measures may aid in the interpretation of scores and the application of such measures to assessing intervention effectiveness.

Needs reflect a desire for certainty and reassurance which cannot be met by the health care system

Longitudinal studies indicate that needs may change over time [25, 49, 50]. However, it is not clear from intervention studies whether needs can be reduced more rapidly or by a greater magnitude by intervention. Potentially life-threatening illnesses such as cancer are associated with high levels of uncertainty [51]. It is plausible that this uncertainty and desire for reassurance may be expressed as unmet psychological or information needs. If this is the case, it is possible that no amount of information, support, or service provision will be able to address this need. Therefore, during some phases of the illness trajectory, certain unmet needs may be endemic to the cancer experience [23]. In these circumstances, it may be important for providers to explore patient concerns, acknowledge uncertainties, and provide appropriate reassurance.

Lack of clarity regarding the nature of unmet needs

In addition to considering the possibility that unmet needs may reflect a desire which cannot be met, it is timely to also consider the nature of the concept of unmet need. The concept of “unmet needs” is a relatively new one, and there is little literature regarding the nature of the construct [23]. The concept of unmet needs appears to have arisen in the context of identifying the range of patient experiences which, if addressed, might ameliorate disease-related psychosocial impacts such as depression, anxiety, and poor QoL. While associations between these outcomes are supported by descriptive research [15, 16], there is no evidence of a causal relationship between unmet needs and patient psychosocial outcomes. It is possible that unmet need surveys, while being helpful in identifying particular patient concerns, are not appropriate as a focus for intervention development or outcome measurement.

Future directions

Given that there is increasing attention directed at describing the unmet needs of people with cancer, it is important to establish whether, and if so, how unmet needs can be reduced. There are several areas where future work could inform the development and testing of unmet need interventions. Firstly, to progress work in this field, it is necessary to develop clear guidelines about the scoring of unmet needs scales. Such guidelines should describe how needs should be scored for intervention trials so that it is possible to attribute change in needs to the intervention. This may necessitate examining test–retest reliability at the item level for existing scales. Further, to determine the magnitude of change needed to establish an intervention effect, the issues of sensitivity and clinical significance need to be considered. Unlike measures of anxiety or depression, criterion validity against a gold standard clinical interview cannot be used to determine clinical significance [23]. Greater clarity about the construct of unmet needs and its mechanism of operation would also assist in the development and design of appropriate interventions. One possible way forward may be to examine what level of needs predict future adverse outcomes such as greater health care utilization, poorer QoL, or greater risk of developing depression.

Limitations

It is possible that some relevant articles were missed by the current review. Articles published in languages other than English and unpublished articles, for example, may have been missed. The use of a funnel plot to assess publication bias was considered. However, given the relatively small number of studies included, it is likely that these results would have been unreliable [52].

Conclusions

This review indicates that most intervention trials have reported either no effect or limited effects on cancer patients’ unmet needs. The current literature does not allow conclusions to be drawn about whether these findings reflect problems with measurement, interventions, or sample selection or whether they indicate that needs are endemic parts of the sequelae of a cancer diagnosis. The inconclusive findings of the intervention studies suggest that further studies to describe unmet needs of cancer patients may have limited utility, if it cannot be demonstrated that these needs are modifiable.

References

Carlson LE, Angen M, Cullum J, Goodey E, Koopmans J, Lamont L, MacRae JH, Martin M, Pelletier G, Robinson J, Simpson JSA, Speca M, Tillotson L, Bultz BD (2004) High levels of untreated distress and fatigue in cancer patients. Br J Cancer 90(12):2297–2304. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601887

Zaboraa J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S (2001) The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psycho-Oncology 10(1):19–28

National Breast Cancer Centre and National Cancer Control Initiative (2003) Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of adults with cancer. Available at http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp90synhtm. Accessed 2011

Fitch M (2000) Supportive care for cancer patients. Hosp Q 3(4):39–46

Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Boyes A, Bonevski B, Burton L, Cook P (2000) The unmet supportive care needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer 88(1):226–237. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<226::AID-CNCR30>3.0.CO;2-P

Wen K, Gustafson D (2004) Needs assessment for cancer patients and their families. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2:11. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-2-11

Girgis A, Boyes A, Sanson-Fisher RW, Burrows S (2000) Perceived needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: rural versus urban location. Aust NZ J Public Health 24(2):166–173. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.2000.tb00137.x

Sutherland G, Hill D, Morand M, Pruden M, McLachlan SA (2009) Assessing the unmet supportive care needs of newly diagnosed patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 18(6):577–584. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.00932.x

Tamburini M, Gangeri L, Brunelli C, Boeri P, Borreani C, Bosisio M, Karmann C, Greco M, Miccinesi G, Murru L, Trimigno P (2003) Cancer patients’ needs during hospitalisation: a quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Cancer 3(1):12

Clavarino AM, Lowe JB, Carmont S-A, Balanda K (2002) The needs of cancer patients and their families from rural and remote areas of Queensland. Aust J Rural Heal 10(4):188–195. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00436.x

Lintz K, Moynihan C, Steginga S, Norman A, Eeles R, Huddart R, Dearnaley D, Watson M (2003) Prostate cancer patients’ support and psychological care needs: survey from a non-surgical oncology clinic. Psycho-Oncology 12(8):769–783. doi:10.1002/pon.702

Davis C, Williams P, Redman S, White K, King E (2003) Assessing the practical and psychosocial needs of rural women with early breast cancer in Australia. Soc Work Health Care 36(3):25–36

Soothill K, Morris SM, Harman J, Francis B, Thomas C, McIllmurray MB (2001) The significant unmet needs of cancer patients: probing psychosocial concerns. Support Care Cancer 9(8):597–605. doi:10.1007/s005200100278

Steginga SK, Occhipinti S, Dunn J, Gardiner RA, Heathcote P, Yaxley J (2001) The supportive care needs of men with prostate cancer (2000). Psycho-Oncology 10(1):66–75. doi:10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<66::aid-pon493>3.0.co;2-z

Chen SC, Yu WP, Chu TL, Hung HC, Tsai MC, Liao CT (2010) Prevalence and correlates of supportive care needs in oral cancer patients with and without anxiety during the diagnostic period. Cancer Nurs 33(4):280–289. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181d0b5ef

McDowell ME, Occhipinti S, Ferguson M, Dunn J, Chambers SK (2010) Predictors of change in unmet supportive care needs in cancer. Psychooncology 19(5):508–516. doi:10.1002/pon.1604

Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher R, Girgis A, Burton L, Cook P, Boyes A (2000) Evaluation of an instrument to assess the needs of patients with cancer. Supportive Care Review Group. Cancer 88(1):217–225. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000101)88:1<217::AID-CNCR29>3.0.CO;2-Y

Rainbird KJ, Perkins JJ, Sanson-Fisher RW (2005) The Needs Assessment for Advanced Cancer Patients (NA-ACP): a measure of the perceived needs of patients with advanced, incurable cancer. a study of validity, reliability and acceptability. Psychooncology 14(4):297–306. doi:10.1002/pon.845

Campbell HS, Sanson-Fisher R, Turner D, Hayward L, Wang XS, Taylor-Brown J (2010) Psychometric properties of cancer survivors’ unmet needs survey. Support Care Cancer 19(2):221–230. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0806-0

Carey M, Clinton-McHarg T, Sanson-Fisher R, Shakeshaft A (2011) Development of cancer needs questionnaire for parents and carers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Support Care in Cancer. doi:10.1007/s00520-011-1172-2

Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C (2011) The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psycho-Oncology 20(4):387–393. doi:10.1002/pon.1740

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hobbs KM, Hunt GE, Lo SK, Wain G (2007) Assessing unmet supportive care needs in partners of cancer survivors: the development and evaluation of the Cancer Survivors’ Partners Unmet Needs measure (CaSPUN). Psycho-Oncology 16(9):805–813. doi:10.1002/pon.1138

Sanson Fisher R, Carey M, Paul CL (2009) Measuring the unmet needs of those with cancer: a critical overview. Cancer Forum 33(3)

Curry C, Cossich T, Matthews JP, Beresford J, McLachlan SA (2002) Uptake of psychosocial referrals in an outpatient cancer setting: improving service accessibility via the referral process. Support Care Cancer 10(7):549–555. doi:10.1007/s00520-002-0371-2

Minstrell M, Winzenberg T, Rankin N, Hughes C, Walker J (2008) Supportive care of rural women with breast cancer in Tasmania, Australia: changing needs over time. Psychooncology 17(1):58–65. doi:10.1002/pon.1174

Campbell HS, Sanson-Fisher R, Taylor-Brown J, Hayward L, Wang XS, Turner D (2009) The cancer support person’s unmet needs survey: psychometric properties. Cancer 115(14):3351–3359. doi:10.1002/cncr.24386

Tamburini M, Gangeri L, Brunelli C, Beltrami E, Boeri P, Borreani C, Fusco Karmann C, Greco M, Miccinesi G, Murru L, Trimigno P (2000) Assessment of hospitalised cancer patients’ needs by the Needs Evaluation Questionnaire. Ann Oncol 11(1):31–37

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (2007) Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC). Data collection checklist. Available at http://epoc.cochrane.org/sites/epoc.cochrane.org/files/uploads/datacollectionchecklist.pdf. Accessed 12 April 2011

White VM, Macvean ML, Grogan S, D’Este C, Akkerman D, Leropoli S, Hill DJ, Sanson-Fisher R (2011) Can a tailored, needs based intervention delivered by volunteers reduce the needs, anxiety and depression of people with colorectal cancer? A randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. doi:10.1002/pon.2019

Aranda S, Schofield P, Weih L, Milne D, Yates P, Faulkner R (2006) Meeting the support and information needs of women with advanced breast cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 95(6):667–673. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6603320

Girgis A, Breen S, Stacey F, Lecathelinais C (2009) Impact of two supportive care interventions on anxiety, depression, quality of life, and unmet needs in patients with nonlocalized breast and colorectal cancers. J Clin Oncol 27(36):6180–6190. doi:10.1200/jco.2009.22.8718

King M, Jones L, McCarthy O, Rogers M, Richardson A, Williams R, Tookman A, Nazareth I (2009) Development and pilot evaluation of a complex intervention to improve experienced continuity of care in patients with cancer. Br J Cancer 100(2):274–280. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604836

Scandrett KG, Reitschuler-Cross EB, Nelson L, Sanger JA, Feigon M, Boyd E, Chang CH, Paice JA, Hauser JM, Chamkin A, Balfour P, Stolbunov A, Bennett CL, Emanuel LL (2010) Feasibility and effectiveness of the NEST13+ as a screening tool for advanced illness care needs. J Palliat Med 13(2):161–169. doi:10.1089/jpm.2009.0170

Macvean ML, White VM, Pratt S, Grogan S, Sanson-Fisher R (2007) Reducing the unmet needs of patients with colorectal cancer: a feasibility study of The Pathfinder Volunteer Program. Support Care Cancer 15(3):293–299. doi:10.1007/s00520-006-0128-4

McLachlan SA, Allenby A, Matthews J, Wirth A, Kissane D, Bishop M, Beresford J, Zalcberg J (2001) Randomized trial of coordinated psychosocial interventions based on patient self-assessments versus standard care to improve the psychosocial functioning of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 19(21):4117–4125

Boyes A, Newell S, Girgis A, McElduff P, Sanson-Fisher R (2006) Does routine assessment and real-time feedback improve cancer patients’ psychosocial well-being? Eur J Cancer Care 15(2):163–171. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00633.x

Allen SM, Shah AC, Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Ciambrone D, Hogan J, Mor V (2002) A problem-solving approach to stress reduction among younger women with breast carcinoma—a randomized controlled trial. Cancer 94(12):3089–3100. doi:10.1002/cncr.10586

Sanson-Fisher RW, Campbell EM, Htun AT, Bailey LJ, Millar CJ (2008) We are what we do: research outputs of public health. Am J Prevent Med 35(4):380–385

Boyes A, Girgis A, Lecathelinais C (2009) Brief assessment of adult cancer patients’ perceived needs: development and validation of the 34-item Supportive Care Needs Survey (SCNS-SF34). J Eval Clin Pract 15(4):602–606. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01057.x

Pearce NJ, Sanson-Fisher R, Campbell HS (2008) Measuring quality of life in cancer survivors: a methodological review of existing scales. Psycho-Oncology 17(7):629–640. doi:10.1002/pon.1281

Boyes A, Hodgkinson K, Aldridge L, Turner J (2009) Issues for cancer survivors in Australia. Cancer Forum 33(3):164–167

Twombly R (2004) What’s in a name: who is a cancer survivor? J Natl Cancer Inst 96(19):1414–1415. doi:10.1093/jnci/96.19.1414

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2005) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in translation. The National Academies Press, Washington

Wen K, McTavish F, Kreps G, Wise M, Gustafson D (2011) From diagnosis to death: a case study of coping with breast cancer as seen through online discussion group messages. J Comput-Mediat Commun 16(2):331–361. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01542.x

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Lo SK, Wain G (2007) The development and evaluation of a measure to assess cancer survivors’ unmet supportive care needs: the CaSUN (Cancer Survivors’ Unmet Needs measure). Psychooncology 16(9):796–804. doi:10.1002/pon.1137

McElduff P, Boyes A, Zucca A, Girgis A (2004) Supportive care needs survey: a guide to administration, scoring and analysis. Centre for Health Research and Psycho-oncology, Newcastle

Rehse B, Pukrop R (2003) Effects of psychosocial interventions on quality of life in adult cancer patients: meta-analysis of 37 published controlled outcomes studies. Patient Educ Couns 50:179–186

Coyne JC, Lepore SJ, Palmer SC (2006) Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in cancer care: evidence is weaker than it first looks. Ann Behav Med 32(2):104–110. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm3202_5

Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, Palmer N, Ream E, Young A, Richardson A, Armes J, Crowe M, Colbourne L, Morgan H, Murrells T, Oakley C, Palmer N, Ream E, Young A, Richardson A (2009) Patients’ supportive care needs beyond the end of cancer treatment: a prospective, longitudinal survey. J Clin Oncol 27(36):6172–6179. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5151

Mor V, Masterson-Allen S, Houts P, Siegel K (1992) The changing needs of patients with cancer at home. A longitudinal view. Cancer 69(3):829–838. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19920201

Garofalo JP, Choppala S, Hamann HA, Gjerde J (2009) Uncertainty during the transition from cancer patient to survivor. Cancer Nurs 32(4):E8–E14. doi:10.1097/NCC.1090b1013e31819f31811aab, 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819f1aab

Sedgwick P (2011) Meta-analyses: funnel plots. BMJ 343. doi:10.1136/bmj.d5372

Acknowledgements

Dr. Mariko Carey is supported by a Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) postdoctoral fellowship, Dr Sylvie Lambert is supported by a NHMRC training fellowship, and Dr. Tara Clinton-McHarg is supported by a Leukaemia Foundation Australia postdoctoral fellowship.

Disclosures

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Carey, M., Lambert, S., Smits, R. et al. The unfulfilled promise: a systematic review of interventions to reduce the unmet supportive care needs of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 20, 207–219 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1327-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1327-1