Abstract

In healthy subjects expiratory flow limitation (EFL) during exercise can lower O2 delivery to the working muscles. We hypothesized that if this affects exercise performance it should influence O2 kinetics at the end of exercise when the O2 debt is repaid. We performed an incremental exercise test on six healthy males with a Starling resistor in the expiratory line limiting expiratory flow to ∼ 1 l s−1 to determine maximal EFL exercise workload (W max). In two more square-wave exercise runs subjects exercised with and without EFL at W max for 6 min, while measuring arterial O2 saturation (% SaO2), end-tidal pressure of CO2 (P ETCO2) and breath-by-breath O2 consumption \({({\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2})}\) taking into account changes in O2 stored in the lungs. Over the last minute of EFL exercise, mean P ETCO2 (54.7 ± 9.9 mmHg) was significantly higher (P < 0.05) compared to control (41.4 ± 3.9 mmHg). At the end of EFL exercise %SaO2 fell significantly by 4 ± 3%. When exercise stopped, EFL was removed, and we continued to measure \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}.}\) During recovery, there was an immediate step increase in \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2},}\) so that repayment of EFL O2 debt started at a higher \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) than control. Recovery \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) kinetics after EFL exercise was best characterized by a double-exponential function with fundamental and slow time constants of 27 ± 11 and 1,020 ± 305 s, compared to control values of 41 ± 10 and 1,358 ± 320 s, respectively. EFL O2 debt was 52 ± 22% greater than control (2.19 ± 0.58 vs. 1.49 ± 0.38 l). We conclude that EFL exercise increases the O2 debt and leads to hypoxemia in part due to hypercapnia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In spite of the fact that dynamic hyperinflation (Calverley and Koulouris 2004; O’Donnell et al. 2001) and peripheral muscle deconditioning (Maltais et al. 1998; Richardson et al. 1999) are important factors limiting exercise in COPD, there is evidence that inadequate oxygen delivery to working locomotor and respiratory muscles may also play an important role (Aliverti and Macklem 2001; Aliverti et al. 2005a; Iandelli et al. 2002).

This situation has been modeled in normal humans by imposing expiratory flow-limitation (EFL) during exercise which limits exercise performance by intense dyspnea (Aliverti et al. 2002; Iandelli et al. 2002), while decreasing arterial oxygen saturation and cardiac output (Aliverti et al. 2005a). This in turn leads to premature competition between respiratory and locomotor muscles for available energy supplies and the early onset of mixed respiratory and metabolic acidosis (Aliverti and Macklem 2001; Kayser et al. 1997).

As a result of these previous experiments (Aliverti and Macklem 2001; Aliverti et al. 2005a; Kayser et al. 1997) we predicted that EFL exercise in normal subjects should increase the oxygen debt by decreasing systemic oxygen delivery to exercising muscles. Accordingly, to test this hypothesis, we measured O2 kinetics during repayment of the O2 debt after control and EFL exercise in young, normal, male subjects. Our results revealed that EFL increased O2 net debt by an average 52% and led to hypoxemia in part due to hypercapnia.

Material and methods

Subjects

We studied six healthy male individuals whose baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. All subjects gave signed–informed consent and the protocol was approved by the University of Athens Ethics Committee, where the experiments were conducted.

Pulmonary function tests

Spirometry for the determination of forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) was performed by a V max 229 system (Sensor Medics, Anaheim, CA, USA) (Table 1).

Exercise protocols

Three exercise tests were performed for each subject on an electromagnetically braked cycle ergometer (Ergoline 800, Sensor Medics) with the subjects maintaining a pedaling frequency of 60 rpm. At the beginning an incremental test was performed to establish the individual subject’s maximal workload when EFL was imposed \(\left({{W}_{\hbox{max}}}_{{\hbox{EFL}}}\right)\) by the application of a Starling resistor in the expiratory line limiting flow to approximately 1 l s−1. After 3 min of baseline measurements, followed by 3 min of unloaded pedaling, the work rate was increased every min by 20 W to the limit of tolerance (i.e. the point where the work rate could not be tolerated due to severe sensation of dyspnea, see Table 1). On a separate day, two square-wave protocols were performed: the first without EFL (control) and the second with EFL. After 3 min of baseline measurements, followed by 3 min of unloaded pedaling, the work rate was set and maintained at \(\left({{W}_{\hbox{max}}}_{{\hbox{EFL}}}\right)\) for 6 min in both protocols. At the end of exercise, EFL was removed and recovery was monitored for an additional 6 min (Fig. 1).

Typical example of volume changes of the chest wall during 3 min of baseline measurements (QB quiet breathing), 3 min of unloaded cycling (W/u warming up), 6 min of exercise at the pre-determined \(\left({{W}_{\hbox{max}}}_{{\hbox{EFL}}}\right)\), and 6 min of recovery. Arrows indicate end of expiration and inspiration. Data acquisition was interrupted for 1 min every 2 min in order to allow data storage

Gas exchange and flow measurements

Instantaneous inspired and expired O2 and CO2 concentrations, end-tidal values for O2 and CO2 (P ETO2, P ETCO2, respectively) and flow at the mouth were recorded breath-by-breath (V max 229, Sensor Medics) throughout both control and EFL exercise and recovery runs. Flow displaced at the mouth was also measured by a screen type pneumotachograph (3813 Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO, USA) and from these measurements the following parameters were obtained: minute ventilation, \(({\dot{V}}_{\rm E});\) tidal volume, (V T); breathing frequency, (f b); inspiratory (T i), expiratory (T e), total respiratory (T tot) cycle time; and duty cycle (T i/Tot). Cardiac frequency (f c) and percentage arterial oxygen saturation (% SaO2) were determined using the R–R interval from a 12-lead on-line electrocardiogram (Marquette Max, Marquette Hellige GmbH, Germany) and a pulse oximeter (Nonin 8600, Nonin Medical, USA), respectively. The modified Borg Scale (Borg 1982) was used to rate the magnitude of dyspnea and leg discomfort every 2 min throughout exercise.

Operational chest-wall volume measurements

Simultaneously, throughout the square wave exercise and recovery protocols the volume of the chest wall was measured by optoelectronic plethysmography (OEP system, BTS, Milan, Italy) as previously described (Aliverti et al. 1997; Cala et al. 1996; Vogiatzis et al. 2005). In brief, the motion of 89 retro-reflective markers placed front and back over the chest wall from clavicles to pubis was recorded. Each marker was tracked by six video cameras, three in front of the subject and three behind. Subjects grasped handles positioned at mid-sternum level, which lifted the arms away from the rib cage, so that lateral markers could be visualized. Dedicated software, which recognizes the markers on each camera in real time, reconstructed their 3D co-ordinates by stereophotogrammetry and using Gauss’s theorem, calculated inspiratory and expiratory tidal volume variations. Thus, breathing pattern was measured both plethysmographically and by integration of flow. Data acquisition from the OEP system was interrupted for 1 min every 2 min (Fig. 1) in order to allow data storage.

Calculation of breath-by-breath oxygen consumption

The volume of O2 exchanged at the mouth differs from the volume of O2 taken up by pulmonary capillaries if the amount of O2 stored within the lung changes. This occurs if the volume inspired is different from the volume expired in a given respiratory cycle, and/or if alveolar concentrations of O2 change (Capelli et al. 2001). This is particularly important during on- and off-exercise transients (Cautero et al. 2002). The changes in O2 stored within the lung must be subtracted from the volume of O2 exchanged at the mouth in order to obtain the amount of O2 exchanged at the alveolar level. This can be done by combining OEP with independent measures of the subdivisions of lung volume and continuously measuring changes in the absolute gas volume by OEP throughout all exercise tests. This method was recently described in detail (Aliverti et al. 2004a, 2005a). Accordingly, in the present study, breath-by-breath oxygen consumption \({( {\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2})}\) was computed throughout using the data acquired by OEP, flow at the mouth and the continuous inspired and expired O2 and CO2 concentration recordings. Using this method corrections were made for (1) pneumotachograph integrator drift, (2) the sampling rates of the O2 and CO2 meters, (3) the time delay of the O2 analyzer and the flow through the O2 and CO2 sampling lines, (4) precise synchronization of O2 concentration and volume signals and (5) any changes in O2 stored within the lung. Thus, in contrast to commercial devices, we measured \({ {\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) at the level of the pulmonary capillaries, not at the mouth.

Curve fitting

To characterize the kinetics of the \({ {\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) response during square-wave exercise and recovery single and double-exponential functions were applied, respectively, to the data using a non-linear least-squares fitting procedure (Figs. 2, 3) without omitting the first 20 s of the response for either the on- or off-transient. The equations applied (Linnarsson 1974; Ozyener et al. 2001) were

where in Eq. 2, the response is the sum of two components, each described by an exponential decay with two time constants: τ1 = 1/b (the fundamental \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) component) and τ2 = 1/d (the slow \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) component). In the same equation, a and c are the initial values of these two components and their sum (a + c) represents the initial value of the total response, i.e. the value of \({ {\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) at time zero. The adequacy of the fitting model was tested by calculating R 2 values and residuals for single and double exponentials.

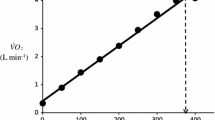

Measurement of oxygen debt

Oxygen debt was calculated by integrating, for each subject, the fitting curves between time zero (start of recovery) and an arbitrary time of 400 s (Fig. 3) Then, the value of mean \({ {\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) at baseline, multiplied by the same period of time, was subtracted (Aliverti et al. 2005a).

Estimation of cardiac output and arterio-venous oxygen difference

To estimate the cardiac output (CO) and the arterio-venous oxygen (a-v O2) difference during EFL and control exercise the following equations (Stringer et al. 1997) were used:

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Significant differences in recorded variables over the last minute of the square-wave exercise protocols between control and EFL tests were assessed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test as were recovery data from control and EFL exercise tests. Linear regression analysis was performed using the least-squares method. A statistical significance of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Results

Square-wave protocols

Figure 2 displays a typical example of breath-by-breath \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) during control and EFL exercise protocols. Individual and mean values of \(\left({{W}_{\hbox{max}}}_{{\hbox{EFL}}}\right)\) sustained during the two square-wave protocols are shown in Table 1, whereas the gas exchange and ventilatory pattern parameters are shown in Table 2. \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) tended to be lower (by 8 ± 2%) at the end of EFL compared to control exercise, albeit not significantly (Table 2). However, EFL compared to control exercise was associated with significantly lower values for \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{CO}_{2},{\dot{V}}_{\rm E}},\) f b, and T i/Tot. T e at the end of EFL exercise was significantly higher compared to control (Table 2). Over the last minute of EFL exercise, mean values for f c, P ETCO2 (54.7 ± 9.9 mmHg) and dyspnea scores were significantly larger compared to control exercise (Fig. 4), whereas mean P ETO2 (87.0 ± 11.3 mmHg) was significantly lower (Fig. 4). The mean fall (P = 0.044) in %SaO2 at the end of EFL exercise was 4 ± 3%. (Fig. 4). Leg discomfort at the end of EFL exercise was not different to that at the end of control exercise (Fig. 4). The on-transient data were best fitted with a mono-exponential function where the time constant of the fundamental \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) component was not significantly different during EFL exercise as compared to control exercise (Table 3).

Recovery oxygen kinetics and oxygen debt

Figure 3 displays a typical example of breath-by-breath \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) data fitted with a double-exponential function during recovery from control and EFL exercise square-wave tests. The R 2 values of the fitted curves applied to the recovery breath-by-breath \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) data were not significantly different between EFL (0.89 ± 0.07) and control exercise (0.86 ± 0.09). Immediately after removing the Starling resistor at the end of EFL exercise there was a step increase in \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2},}\) so that repayment of O2 debt started at a higher \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) after EFL than control. Figure 5 demonstrates individual values of the a, c, and a + c parameters obtained from Eq. 2. All three parameters were significantly higher after EFL compared to control exercise (a: P = 0.04; c: P = 0.0002; a + c: P = 0.02). Also shown in Fig. 5 is the total O2 debt which was 2.19 ± 0.58 l after EFL exercise compared to the control value of 1.49 ± 0.38 l, an increase of 52 ± 22% (P = 0.01) caused by EFL. In order to verify possible problems originated by the curve fitting, oxygen debt and deficit were also calculated directly from the original breath-by-breath data and did not differ significantly compared to the data obtained by the fitted curves (average difference 4.3 ± 3.1%).

Individual values of the parameters given in Eq. 1: a (a), c (b), a + c (c) and calculated gross values for the oxygen debt (d) after the EFL and control exercise protocols

Individual and mean values for the off-transient time constants of the fundamental and slow \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) components are shown in Table 3. The fundamental time constant was significantly (P = 0.028) shorter during recovery from EFL compared to control exercise (Table 3). The off-transient slow component during recovery from EFL tended (P = 0.068) to be shorter compared to that after control exercise; however, in recovery from control exercise the slow component was not evident in subjects 3 and 4 (Table 3). Table 4 reports the individual and mean data of the on and off \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) transients for EFL and control exercise.

Estimation of cardiac output and arterio-venous oxygen difference

From Eq. 3), COEFL = [1.9 l min−1/5.72 + (0.105 × 95 Footnote 1)] = 12.5 l min−1.

From Eq. 4, a-v O2EFL = 5.72 + (0.105 × 95) = 15.2 ml O2 per 100 ml of blood. In addition, a-v O2control = 5.72 + (0.10 × 60 Footnote 2) = 5.72 + 5.9 = 11.7 ml O2 per 100 ml of blood.

Based on the above calculations, the mixed venous blood O2 content (C vO2) for EFL would be equivalent to 4.8 ml per 100 ml blood or 48 ml O2 l−1. For control, C vO2 would be equivalent to 8.3 ml O2 per 100 ml blood or 83 ml O2 l−1.

Taking into account that 70% of blood volume is located in the venous compartment at rest and during moderate exercise that figure falls to approximately 50% (Astrand and Rodahl 1986), then during EFL exercise with a cardiac output of 12.5 l min−1 the C vO2 will be [(12.5 l min−1 × 0.5) × 0.048 l O2] = 0.3 l or 300 ml O2. For control exercise, the C vO2 will be [(13.75 l min−1 × 0.5) × 0.083 lO2] = 0.57 l or 570 ml O2. Thus, the difference in C vO2 between EFL and control will be 570 − 300 = 270 ml. Hence from the 0.70 l difference in oxygen debt between EFL and control calculated in Table 5 (2.19 − 1.49 = 0.70 l), 0.27 l (i.e. approximately one-third) would account for the replenishment of the blood oxygen stores.

Discussion

There is growing evidence that an inadequate oxygen supply to meet demand may play a more dominant role in limiting exercise capacity in some patients with advanced COPD than impaired lung function (Aliverti et al. 2004b, 2005b; Maltais et al. 1998; Oelberg et al. 1998; Potter et al. 1971; Richardson et al. 1999; Stark-Leyva et al. 2004). In healthy subjects, limiting expiratory flow by a Starling resistor or increasing expiratory load by imposing a constant pressure at the mouth during expiration, have been shown to significantly reduce cardiac output during exercise (Aliverti et al. 2005a; Stark-Leyva et al. 2004). This results from the enforced decrease in the velocity of shortening of expiratory muscles and hypercapnia, both of which contribute to increased expiratory muscle force and decreased duty cycle so that expiration acts like a Valsalva maneuver with inadequate time to recover during inspiration (Aliverti et al. 2002, 2005a; Iandelli et al. 2002). Furthermore, the decreased duty cycle magnifies the effect of high expiratory pressures when averaged over the whole respiratory cycle. Our present results show that EFL increased O2 debt by an average 52% and led to hypoxemia in part due to hypercapnia. This supports our hypothesis that the reduction in cardiac output during EFL exercise decreases O2 supply to working locomotor and respiratory muscles resulting in an increased O2 debt. We conclude that the decreased cardiac output is important in limiting EFL exercise performance in healthy subjects.

EFL as a model for COPD

The experimental model used in this study was designed to simulate, in part, the flow-limitation commonly experienced by COPD patients during exercise. The pros and cons of this model have been previously extensively discussed (Aliverti et al. 2002; Iandelli et al. 2002). The model has demonstrated that exercise with EFL induces intolerable dyspnea, CO2 retention, impaired exercise performance, expiratory muscle recruitment (Kayser et al. 1997), blood shifts from trunk extremities, a reduced duty cycle, arterial desaturation, and a decrease in cardiac output (Aliverti et al. 2005a).

In the present study, we confirmed many of these results and showed that the increased O2 debt was accompanied by a reduction in \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) by 8% and a fall in SaO2 by 4% at the end of EFL exercise, thus leading to a reduction in systemic O2 delivery of ∼ 12%, in close agreement with the 15% reduction reported by Aliverti et al. (2005a). It is reasonable to assume that the reduction in systemic O2 delivery during EFL exercise would be associated with the progressive recruitment of fast-twitch fibers and hence the premature onset of the lactate threshold. The latter has been shown to be the case during exercise with EFL (Aliverti et al. 2005a). When exercise workloads exceed the lactate threshold, energy supplies are inadequate to meet demands. The resulting competition between working locomotor and respiratory muscles for the available energy supplies, regulated by autonomic reflex mechanisms (Harms et al. 1998), would be substantially worsened by the decrease in the available O2 and should further increase the lactate production. It is therefore likely that the muscle and blood lactate levels (not measured in the present study) would be appreciably higher during EFL exercise and consequently, the lactate related metabolic cost could significantly contribute to the repayment of the O2 debt in recovery from EFL exercise.

In addition to the reduction in systemic O2 delivery, the present study shows that application of EFL during exercise significantly decreased minute ventilation compared to control exercise, causing hypercapnia. This confirms earlier results that show that a vicious circle is induced whereby increasing central ventilatory drive increases expiratory pressure which further reduces alveolar ventilation and cardiac output (Aliverti et al. 2002, 2005a; Iandelli et al. 2002). Furthermore, the observed elevated heart rate during EFL exercise possibly reflects a reduction in stroke volume secondary to the decrease in venous return. In the study by Stark-Leyva et al. (2004), expiratory loading during exercise increased heart rate in an attempt to minimize the effects of the reduced stroke volume on cardiac output. Thus, the reduced cardiac output secondary to the high expiratory pressures would also be expected to contribute importantly to the greater oxygen debt that was measured after EFL exercise.

In summary, EFL exercise in healthy subjects reproduces many features of COPD including acute respiratory failure, a condition resembling cor pulmonale, dyspnea, and impairment of exercise performance. Furthermore, it has led to testable predictions, one of which is the rationale for this study and which to date have been proven to be accurate (Aliverti et al. 2004b, 2005a, b).

Off-transient O2 kinetics

The increase in O2 debt by 52% that we found during EFL exercise impacted, as predicted, on O2 kinetics during recovery. Accordingly, the repayment of O2 debt after EFL exercise started at a higher \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) compared to control and the off-transient time constant of the fundamental and slow \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) components were shorter after EFL exercise. Collectively, the findings describing the EFL off-transient O2 kinetics reflect a more rapid replenishment of blood O2 stores (fundamental component) and a faster repayment of O2 tissue debt (slow component), both of which could result from the greater O2 deficit during EFL exercise as opposed to control exercise. Indeed, if we considered that cardiac output during EFL exercise was lower than control and \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) was not significantly different between EFL and control, then it would be reasonable to expect that during exercise with EFL, that is known to decrease pulmonary blood flow (Aliverti et al. 2005a), the arterial to mixed venous blood O2 difference would be larger and the mixed venous blood O2 content would be lower. This notion was confirmed by our calculations of arterial to mixed venous blood O2. When at the end of exercise EFL was removed, the sudden increase in cardiac output and in blood perfusing the lungs brought about a refilling of the O2 stores of mixed venous blood; hence the sudden increase of \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) (marking the replenishment of the body’s deprived oxygen stores), a faster \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) kinetics and a larger O2 debt in EFL (Table 5). The larger depletion of the inner oxygen stores is also suggested by the longer time constants of the on- and off-transient \({{\dot{V}} {O}_{2}}\) response during EFL exercise (Table 3). Our calculations showed that approximately 30% of the O2 debt difference between EFL and control exercise was due to the blood O2 replenishment (Table 5) caused by the reduced cardiac output during EFL, whereas the rest was due to other possible mechanisms described below.

In line with the results of Cunningham et al. (2000) and Ozyener et al. (2001) describing O2 kinetics after heavy exercise, the off-transient \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) data after EFL exercise were best fitted by a two component exponential function. The fundamental off-transient component after control exercise (40.6 s) was similar to that (∼ 33 s) described by Cunningham et al. (2000) and Ozyener et al. (2001) following very heavy exercise, lasting as in the present study for 6 min. On the other hand, the time constant of the fundamental component after EFL exercise (26.6 s) was significantly shorter than that of control exercise, thus confirming replenishment of the body’s deprived oxygen stores upon removal of EFL. In addition, the shorter time constant calculated after EFL is the result of fitting the data from higher starting points as evidenced by the significantly higher a + c values shown in Table 4 and Fig. 5c.

Furthermore, the time constant of the slow component after EFL exercise (1,020 s) was twofold longer than the one (460 s) described previously for very heavy exercise (Ozyener et al. 2001) possibly reflecting the additive effects of the EFL-induced reduction in systemic O2 delivery on the repayment of tissue O2 debt. Although at present the mechanism(s) of the \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) slow component is not fully understood, there are important factors that could influence the slow component after EFL exercise. These include the blood lactate concentration (Poole et al. 1994), the influence of the metabolic acidosis on the HbO2 dissociation curve (Wasserman et al. 1991), the increased respiratory and cardiac muscle energy requirement associated with EFL exercise (Aaron et al. 1992; Harms et al. 1998), the progressive recruitment of type-II fibers (Coyle et al. 1992) and to a lesser extent the increased levels of circulating catecholamines (Gaesser et al. 1994) associated with the greater cardiovascular response during EFL exercise. Importantly, excessive expiratory muscle recruitment has been shown in patients with airflow limitation to increase the oxygen cost of breathing threefold (Aliverti et al. 2004b). Accordingly, it is reasonable to assume that the higher O2 cost of breathing during EFL exercise would significantly enhance the O2 dept as compared to exercise without EFL.

In the present study, we utilized a double-exponential function to describe the off-transient \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) kinetics not only for EFL exercise but also for control exercise [typically fitted by a mono-exponential function (Cunningham et al. 2000; Ozyener et al. 2001)], in order to allow adequate comparisons of relevant parameters of recovery for both exercise tests. Accordingly, the slow component observed after control exercise was not discernible in two subjects using the double-exponential function. This is in accordance with previously reported data by Cunnnigham et al. (2000) who exercised healthy subjects at a similar work rate (100 W), yielding similar exercise \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) (1.7 l min−1) as the one reached in the present study during control exercise. In conditions where exercise is sustained at a moderate intensity, as in the control test, the off-transient slow component is often not discernible such that \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) kinetics can retain first-order characteristics (Cunnnigham et al. 2000; Gerbino et al. 1996; Ozyener et al. 2001).

In conclusion, the results of the present study provide further evidence that expiratory flow limitation during exercise reduces systemic O2 delivery, enhances the O2 debt and leads to hypoxemia in part due to hypercapnia.

Notes

Mean \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{{\rm 2EFL}}}\) was equivalent to 95% \({{{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}_ {\hbox{max}}}_{{\rm EFL}}\) (2.1 ± 0.4 l min−1) recorded during the incremental test with EFL (see Table 1). Since COEFL has been shown to be 10% lower than COcontrol (Aliverti et al. 2005a), it was estimated that COcontrol was 13.75 l min−1.

Based on previous findings that \({{{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}_ {\hbox{max}}}_{{\rm EFL}}\) is approximately 60% of control \({{{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}_ {\hbox{max}}}\) (Aliverti et al. 2005a) it was estimated that \({{{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}_ {\hbox{max}}}_{{\rm control}}\) would be equivalent to approximately 3.5 l min−1. Therefore, \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) during control exercise (2.1 ± 0.3 l min−1) was equivalent to approximately 60% of control \({{{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}_ {\hbox{max}}}.\)

References

Aaron EA, Seow KC, Johnson BD, Dempsey JA (1992) Oxygen cost of exercise hyperpnea: implications for performance. J Appl Physiol 72:1818–1825

Aliverti A, Macklem PT (2001) How and why exercise is impaired in COPD. Respiration 68(3):229–239

Aliverti A, Cala SJ, Duranti R, Ferrigno G, Kenyon CM, Pedotti A, Scano G, Sliwinski P, Macklem PT, Yan S (1997) Human respiratory muscle actions and control during exercise. J Appl Physiol 83:1256–1269

Aliverti A, Iandelli I, Duranti R, Cala SJ, Kayser B, Kelly S, Misuri G, Pedotti A, Scano G, Sliwinski P, Yan S, Macklem PT (2002) Respiratory muscle dynamics and control during exercise with externally imposed expiratory flow limitation. J Appl Physiol 92:1953–1963

Aliverti A, Kayser B, Maklem PT (2004a) Breath-by-breath assessment of alveolar gas stores and exchange. J Appl Physiol 96(4):1464–1469

Aliverti A, Stevenson N, Dellaca RL, Lo Mauro A, Pedotti A, Calverley PMA (2004b) Regional chest wall volumes during exercise in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax 59(3):210–216

Aliverti A, Dellaca RL, Lotti P, Bertini S, Duranti R, Scano G, Heyman J, Lo Mauro A, Pedotti A, Macklem PT (2005a). Influence of expiratory flow-limitation during exercise on systemic oxygen delivery in humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 95:229–242

Aliverti A, Rodger K, Dellaca RL, Stevenson N, Lo Mauro A, Pedotti A, Calverley PMA (2005b) Effect of salbutamol on lung function and chest wall volumes at rest and during exercise in COPD. Thorax 60(11):916–924

Astrand PO and Rodahl K (1986) Body fluids, blood and circulation, 3rd edn. In: Textbook of work physiology. Physiological bases of exercise. McGraw Hill, New York, pp 127–202

Borg GAV (1982) Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc 14:377–381

Cala SJ, Kenyon CM, Ferrigno G, Carnevali P, Aliverti A, Pedotti A, Macklem PT, Rochester DF (1996) Chest wall and lung volume estimation by optical reflectance motion analysis. J Appl Physiol 81(6):2680–2689

Calverley PMA, Koulouris NG (2004) Flow limitation and dynamic hyperinflation: key concepts in modern respiratory physiology. Eur Respir J 25:186–199

Capelli C, Cautero M, di Prampero PE (2001) New perspectives in breath-by-breath determination of alveolar gas exchange in humans. Pflugers Arch 441:566–577

Cautero M, Beltrami AP, di Prampero PE, Capelli C (2002) Breath-by-breath alveolar oxygen transfer at the onset of step exercise in humans: methodological implications. Eur J Appl Physiol 88:203–213

Coyle EF, Sidosis LS, Horowitz JF, Belttz JD (1992) Cycling efficiency is related to the percentage of type I muscle fibres. Med Sci Sports Exerc 24:782–788

Cunningham DA, Croix CM, Paterson DH, Ozyener F, Whipp BJ (2000) The off-transient pulmonary oxygen uptake kinetics following attainment of a particular oxygen uptake during heavy intensity exercise in humans. Exp Physiol 85:339–347

Gaesser GA, Ward SA, Baum VC, Whipp BJ (1994) Effects of infused epinephrine o slow phase of O2 uptake kinetics during heavy exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 77:2413–2419

Gerbino A, Ward SA, Whipp BJ (1996) Effects of prior exercise on pulmonary gas exchange kinetics during high intensity exercise in humans. J Appl Physiol 80:99–107

Harms CA, Wetter TJ, McClaran SR, Pgelow DF, Nickele GA, Nelson WB, Hanson P, Dempsey JA (1998) Effects of respiratory muscle work on cardiac output and its distribution during maximal exercise. J Appl Physiol 85(2):608–618

Iandelli I, Aliverti A, Kayser B, Dellaca R, Cala SJ, Duranti R, Kelly S, Scano G, Sliwinski P, Yan S, Macklem PT, Pedotti A (2002) Determinant of exercise performance in normal men with externally imposed expiratory flow limitation. J Appl Physiol 92(5):1943–1952

Kayser B, Sliwinski P, Yan S, Tobiasz M, Macklem PT (1997) Respiratory effort during exercise with induced expiratory-flow limitation in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol 83(3):936–947

Linnarsson D (1974) Dynamics of pulmonary gas exchange and heart rate changes at start and end of exercise. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl 415:1–68

Maltais F, Jobin J, Sullivan MJ, Bernard S, Whittom F, Killian KJ, Desmeules M, Belanger M, LeBlanc P (1998) Metabolic and hemodynamic responses of lower limb during exercise in patients with COPD. J Appl Physiol 154:1573–1580

O’Donnell DE, Revill SM, Webb KA (2001) Dynamic hyperinflation and exercise intolerance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164:770–777

Oelberg DA, Medoff BD, Markowitz DH, Pappagianopoulos PP, Ginns LC, Systrom DM (1998) Systemic oxygen extraction during incremental exercise in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur J Appl Physiol 78:201–207

Ozyener F, Rossiter HB, Ward SA, Whipp BJ (2001) Influence of exercise intensity on the on- and off-transient kinetics of pulmonary oxygen uptake in humans. J Physiol 533.3:891–902

Poole DC, Gladden LB, Kurdak S, Hogan MC (1994) Lactate infusion into working dog gastrocnemius: no evidence lactate per se mediates \({{\dot{V}}\hbox{O}_{2}}\) slow component. J Appl Physiol 76:787–792

Potter WA, Olafsson S, Hyatt RE (1971) Ventilatory mechanics and expiratory flow limitation during exercise in patients with obstructive lung disease. J Clin Invest 50:910–919

Richardson RS, Sheldon J, Poole DC, Hopkins SR, Ries AL, Wagner PD (1999) Evidence of skeletal muscle metabolic reserve during whole body exercise in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:881–885

Stark-Leyva KN, Beck KC, Johnson BD (2004) Influence of expiratory loading and hyperinflation on cardiac output during exercise. J Appl Physiol 96(5):1920–1927

Stringer WW, Hansen JE, Wasserman K (1997) Cardiac output estimated noninvasively from oxygen uptake during exercise. J Appl Physiol 82(3):908–912

Vogiatzis I, Aliverti A, Golemati S, Georgiadou O, LoMauro A, Kosmas E, Kastanakis E, Roussos C (2005) Respiratory kinematics by optoelectronic plethysmography during exercise in healthy subjects. Eur J Appl Physiol 93:581–587

Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DY (1991) Facilitation of oxygen consumption by lactic acidosis during exercise. News Phys Sci 6:29–34

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vogiatzis, I., Zakynthinos, S., Georgiadou, O. et al. Oxygen kinetics and debt during recovery from expiratory flow-limited exercise in healthy humans. Eur J Appl Physiol 99, 265–274 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-006-0342-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-006-0342-2